Sylvia Earle: Defender of Oceans—on Her Life, Climate Change, Health, and the Future

An essay and Q&A; also my Vanity Fair essay on how climate change impacts the Ocean microbiome; diving with my son in Belize for Outside; and my UN talk on radical stewardship

Sylvia Earle talking about climate change and the oceans at the recent Sun Valley Forum in Idaho.

In this issue of FUTURES

Theme: Climate Change and the Oceans

New Essay: Sylvia Earle: Defender of Oceans—on Her Life, Climate Change, Health, and the Future, by David Ewing Duncan.

Q&A: Sylvia Earle, PhD

Essay in Vanity Fair: “The Next Climate Change Calamity? We’re Ruining the Microbiome of the Oceans,” By David Ewing Duncan, August 29, 2023

Essay in Outside: “Has Belize Been Spoiled?

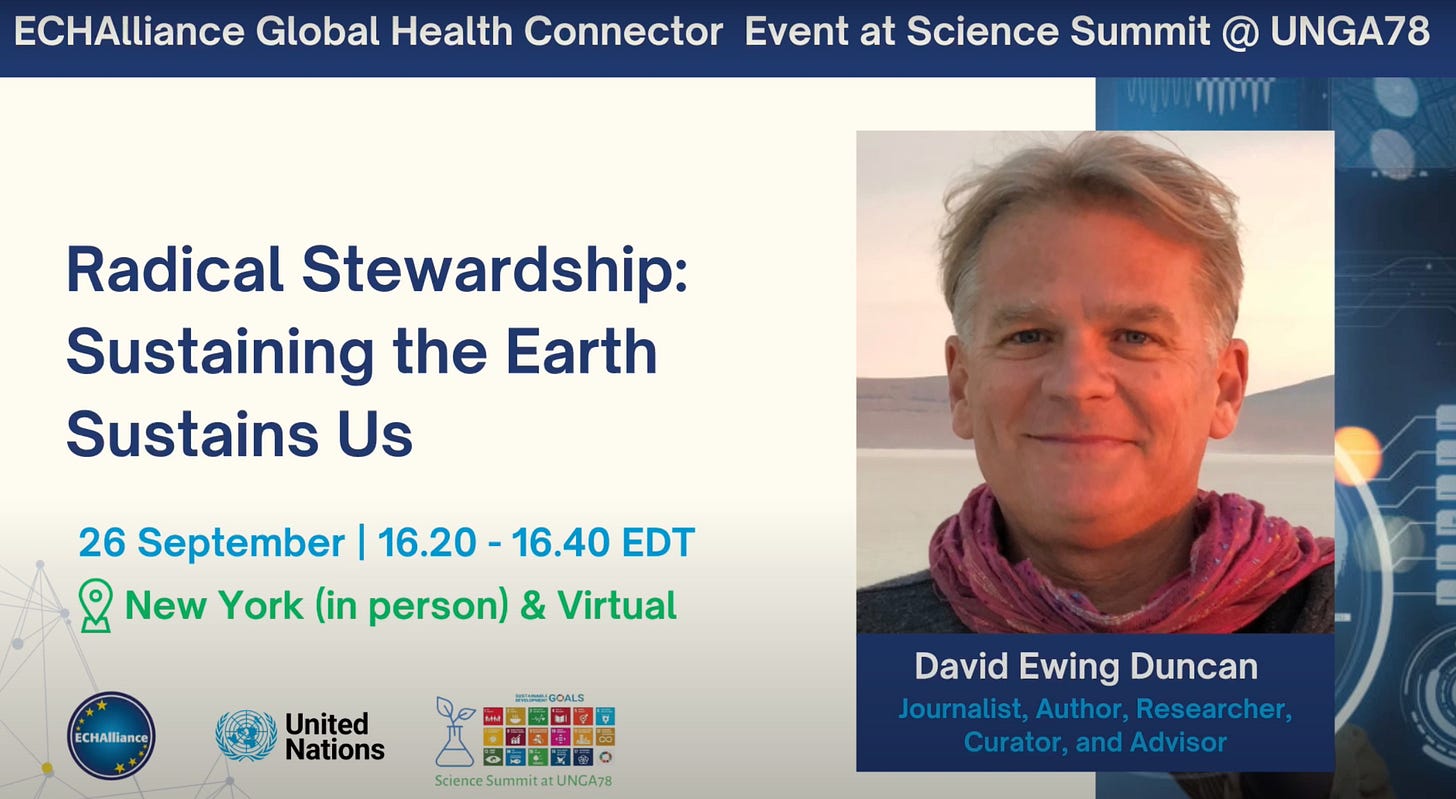

Talk (Video): UN Science Summit: Radical Stewardship: Sustaining the Earth Sustains Us: Talk I gave during Climate Week and the UN Science Summit in 2023.

FUTURES is a column and a newsletter about possible futures at a pivotable moment in history, where the future could turn out wondrous—or not. I’m asking the most interesting people I can find what they are most excited about and most afraid of for the future, and why.

Help Support Futures! If you like the column, join as a paid subscriber for a tiny amount. If you do this in the next 4 weeks, I’ll send you your choice of one of my most recent books—Microlands, on the microbiome of Earth (see below) or Talking to Robots: a Brief Guide to Our Human Robot Futures. (You’ll still get the column free regardless for now). Thanks!

For more stuff check out my website: www.davidewingduncan.com

New Essay

Sylvia Earle: Defender of Oceans—on Her Life, Climate Change, Health and the Future

by David Ewing Duncan, August 26, 2024

“The ocean. The blue heart of the planet.” - Sylvia Earle

When my children were very small, we spent rainy weekends at the National Aquarium in Baltimore’s inner harbor. My son and daughter would rush inside through big glass doors, racing to be the first in to push a big button in the lobby. Embedded on the chest plate of a gangly deep-dive suit on display—it looked like a cross between an astronaut’s suit and Buzz Lightyear—the button activated a face on a video monitor mounted inside the faceplate: the image of a small, bright-eyed woman who came to life when the button was pressed.

I’m pretty sure that this was a video image of Sylvia Earle, welcoming us the aquarium, although it happened so long ago that I’m not sure it was her, and I can’t confirm this. But I’d like to imagine it was her, since even way back in the 1990s Sylvia Earle was already an oceanic legend as a marine biologist, explorer, inventor, writer, television personality, and pioneering woman of science—and as a fierce defender of the great seas that cover two-thirds of our small planet, and of the the vast life they contain. The Earth, she points out, gleams blue from space, not red and arid-looking like Mars, or white and lonely like the moon.

I first met Sylvia Earle in the flesh at TED in 2009 when she was awarded the million-dollar TED Prize (watch her TED talk here). I found myself sitting with her at lunch that week in Long Beach, and was struck by how she speaks. Most people in casual conversation talk in short clips and in sentences filled with commas and semi-colons. Sylvia—she’s so approachable you want to call her by their her name—speaks in beautifully composed, complete sentences and paragraphs delivered in a low, lilting voice that sounds like waves gently lapping.

Where to start? Sylvia Earle is a National Geographic Explorer at Large, the first female chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a co-founder of Deep Ocean Engineering that designed and built deep ocean systems and submersibles, and Time Magazine’s Hero of the Planet in 1998. She was so much more that it would take several paragraphs to cover everything. Currently, she is president and founder of Mission Blue, dedicated to protecting the oceans and to setting up “Hope Spots,” specific stretches of ocean that the group focuses on to defend. Their goal is to protect 30% of the oceans by 2030, working with over two-hundred like-minded organizations.

Sylvia Earle was inspired as a young woman by another famous marine biologist, Rachel Carson. In 2018 Sylvia wrote an introduction to Carson’s 1951 bestseller The Sea Around Us: “Her writings are so sensitive to the feelings of fish, birds and other animals that she could put herself in their place, buoyed by the air or by water, gliding over and under the ocean’s surface. She conveyed the sense that she was the living ocean…” Sylvia could have been writing about herself, too.

This summer, I got to chat with Sylvia Earle again at the Sun Valley Forum. in Ketchum, Idaho. Among other things, we talked about the microbiome of the oceans—the subject of my last book, Microlands: The Future of Life on Earth (and why it’s smaller than you think),* co-authored by Craig Venter. In the interview below, Sylvia talks about the microbiome as being the underpinning of life not only in the oceans, but on all of Earth. She laments that human activity with climate change and pollution and other factors is altering the microbiome of the seas and the planet. In the book, Craig and I write about the impact of climate change on our delicate planet in the last chapter. (Included in this issue of Futures is a Vanity Fair story I wrote last year about the book).

Just last week Sylvia Earle and I exchanged emails as I finished this issue of Futures. She told me she was en route from Auckland to Tonga, where she said she was attending the “annual Pacific Islands Forum where I will be weighing in on the urgent need to protect the High Seas, deep seas and everything in between.” In other words, there is no slowing down for Sylvia Earle at age 88 as she rushes all over our watery planet with the same curious, kind face and fierce resolve that (I think) greeted my children at the National Aquarium all those years ago when they dashed inside to push that button and waited with great anticipation for the woman inside the gangly undersea suit to flash to life and talk about the magic and the wonder of the oceans.

*The title of this book is The Voyage of Sorcerer II: The Expedition that Unlocked the Secrets of the Ocean’s Microbiome in the US edition.

Q&A: Sylvia Earle, PhD

During the Sun Valley Forum on climate change, I got a chance to chat with Sylvia Earle about her long life as a defender of the oceans—and about the future.

I’ll start with the question that I ask everyone for this column. What are you most excited about, and what are you most afraid of for the future and why?

I'm most excited about being a 21st century human being. This is truly a pivotal time as never before. We have the superpower of knowing what nobody could know before, and we have a chance to find a place for ourselves within the natural living systems that make earth habitable. But here's the thing. I heard Ed Wilson say that we're letting nature slip through our fingers.

That’s E.O. Wilson, the entomologist and writer?

Yes, EO Wilson. We have consumed and converted nature. We call it ‘natural resources’ that are meant to foster our prosperity. We have looked at nature as the source of goods, of monetizing nature. A live fish is worth less than a dead fish. We take a forest and then turn it into something more useful to us. You turn a tree into board feet of lumber, or you take the place where the tree is standing and turn it into a useful place for agriculture or for a paved road. Anyway, nature is slipping through our fingers, but the real problem is nature could let us slip through its fingers.

It sounds like you just gave both what you're excited about and afraid of .

I'm afraid there's a complacency born of a profound ignorance and complacency about nature. People don't know why they should care.

Why do you think this is? For one thing, we’ve been able to see the Earth from space since 1968, and it's clearly dominated by…

An ocean? Yes. But it's not just about water. It's about the living systems in the oceans. There's plenty of water elsewhere in the universe, but only here that we have four and a half billion years of rocks and water being transformed mostly by microbes into a planet that is habitable for us and the rest of life. And it's taken us about four and a half decades to unravel those systems.

Rachel Carson talked about the fabric of life—how everything is connected. But science in her time didn’t yet know much about the microbiome of the oceans and the planet, which is literally the fabric of life.

She didn't know what Lynn Margulis came to know about how microbes rule. And how they can turn on a dime, many of them. You change the chemistry of the ocean, you change the acidity, you change the microbes, and then you change everything. And we are doing this through our actions, through excess carbon dioxide becoming carbonic acid in the ocean. What are the consequences? Most people don't realize how much we are in the middle of a big, unplanned experiment.

How would you sum up the many years that you've been doing what you do?

That it's a privilege to be alive, period. And to be a witness to this remarkable era of change, and to feel inspired about the opportunity that we have because of what we now know. It's now taken for granted that you can talk to someone on the other side of the planet. We differ on so many levels, yet we're all united because we're all indigenous to this planet. This is our home, and we all breathe the air, but the choices we make will determine whether we will make it or not as a part of nature.

What do you think?

The natural systems will continue with us or without us. So it’s up to us to work hard to preserve the basic elements that we now cherish about life, about nature—the trees, birds, flowers, the existence of a wild ocean that sustains us and inspires us. We can lose so much so fast if we fail to take care of the last old growth forests. We need natural systems; they are like a library of answers to everything.

Is it a library that we’re paying attention to?

Not enough. We don't know all that much about nature, how it works, but we act as if we do. When I hear sustainability based on us continuing to take ocean wildlife to feed our starving millions, that’s not sustainability. We should be talking about how we find our place within the natural living systems. But there also have been wonderful advancements. For instance, there are now millions of scuba divers. When I was a child, there were a few dozen. That's cause for hope because so many people have experienced what our predecessors could not.

What do you feel when you're under the ocean?

It's like going home. It's diving into the history of life on earth. The ocean is where the greatest diversity and abundance of life is. Probably 80% of the biosphere lives in the dark all of the time in the deep oceans beneath where sunlight shines. In the open ocean, you can find so many major divisions of animal life, much more than on land. And it's not just the animals. There are also photosynthetic organisms, and chemosynthetic organisms. There are microbes everywhere, even where the ocean seems empty, they’re there—so the water itself is alive with information.

What have you discovered recently that just blew your mind—say in the last month?

One thing I’ve been thinking about are what I call the two miracles of how life works. It’s a brilliant strategy of evolution that uses the infinite capacity for diversity to keep life resilient. There are winners and losers. There will be organisms that say: “my time has come, I like this acid ocean, and I'm really going to take off and I will give rise to another whole network of descendants.” Change is constant, although the rate of change that we have imposed is different. We now have technologies that didn’t exist before that give us this superpower of destruction—to take half of the fish out of the ocean in a matter of decades and to consume half of the arable land and convert it to agriculture. I wish I had a time machine to come back in a hundred or a thousand years from now to see what happens.

What advice do you have for us to work for the future you’d like to see?

Lynn Margulis is among those who have said we have progressed from one generation to the next because we cooperated. I believe this needs to include cooperating with nature. Instead of beating the other guy out, we progress by sharing what we know. It's where we come together to solve problems. How do we conquer disease? How do we conquer ignorance? How do we conquer our own desires, our inner chimpanzee that is more warlike than our inner bonobo that is more peaceful, more caring, more collaborative? I believe if we follow our better nature, we will figure it out.

________

Essay

From my archives: How climate change is altering the microbiome of the oceans, and the Earth—and why that’s bad—in Vanity Fair

The Next Climate Change Calamity? We’re Ruining the Microbiome, According to Human-Genome-Pioneer Craig Venter

In a new book (coauthored with Venter), a Vanity Fair contributor presents the oceanic evidence that human activity is altering the fabric of life on a microscopic scale.

By David Ewing Duncan, Vanity Fair, August 29, 2023

Human activity is causing a huge imbalance in the global microbiome,” said Craig Venter in his low, rumbling voice. As usual, he was not mincing words. It was 2018. Venter and I were sitting on the deck of Sorcerer II, his 100-foot sailboat, sipping coffee on a cold, misty morning in the Gulf of Maine. Slow, looping waves surrounded the boat as dolphins, off the starboard, leaped up and down in great arcs, their sleek, gray bodies lathered in foam.

What Venter meant is that fossil fuels and other pollutants aren’t just messing with polar bears and Monarch butterflies. They are also changing the invisible world of tiny organisms that sustain life as we know it, something that’s integral to what Rachel Carson called “the fabric of life” in her seminal 1962 book, Silent Spring, an indictment of humans’ folly in polluting their own environment.

This warning has become Venter’s clarion call too. It is a central theme of a new book that he and I have cowritten called The Voyage of Sorcerer II: The Expedition That Unlocked the Secrets of the Ocean’s Microbiome, which lays out the compelling evidence of how Homo sapiens are causing the micro-fabric of our lives to come apart at the seams.

For the rest of this essay, go here.

Microlands: The Future of Life on Earth (and why it’s smaller than you think), by J. Craig Venter and David Ewing Duncan (LittleBrownUK—Harvard U Press-USA). Order Here

“Will shape our understanding of the global ecosystem for decades to come.”―Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies

________

Essay

From my archives: A magical diving trip to Belize with my son 27 years after I thought I might have ruined this tiny country and its stunning ocean reefs—in Outside

Alex Duncan, age 18, diving with me off the coast of Belize at 75 feet in 2014.

Has Belize Been Spoiled?

In 1987, the author wrote a magazine article about a secret tropical gem called Belize, inspiring a wave of adventure travelers that changed the tiny country forever. Braced for a few stabs of guilt, he went back with his son and found that paradise was different, but not completely lost.

By David Ewing Duncan, Outside, March 5, 2014

Mostly I remember the ocean’s sharp blue phosphorescence. Looking like a patch of water that Jesus might walk on, it stretched with hardly a ripple from the beach out to a wall of frothing surf just off the coast. That’s where one of the finest coral reefs in the world lay submerged below the surface, a diver’s magic kingdom beckoning.

This memory comes from my first trip to Ambergris Caye, in 1987, back when few outsiders knew about this idyll off the Belizean coast…

Now, 26 years later, I was back, about to tumble backward off a dive boat into those same weirdly glowing waters. I had returned to spend some time with my 18-year-old son, Alex, before he left for college—and, I suppose, to revisit memories logged by my twentysomething self.

Mostly, though, I was back to revisit the scene of my crime.

For the rest of this essay, go here.

________