The Biophysicist, the Billionaire, and the Quest to Cure Disease—an Update

Mark Zuckerberg & Priscilla Chan tapped Stanford's Steve Quake to help eradicate disease by 2100. How's it going? Also: The Future of Health (report); Zuckerberg at age 22: a 2006 interview (podcast)

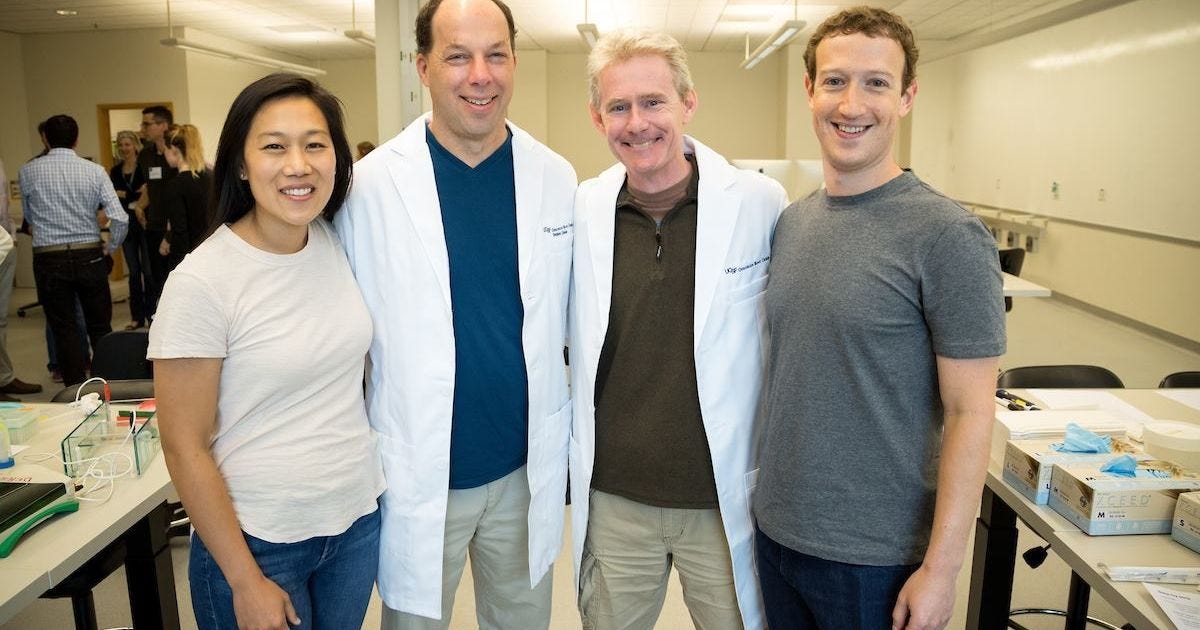

Biophysicist and Head Scientist for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Steve Quake (Second from L) in the Chan Zuckerberg BioHub in San Francisco. With co-founder and co-CEO Priscilla Chan; Biohub co-president and molecular biologist Joe DiRisi; and co-founder and co-CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

In this issue of FUTURES

Theme: Can We Cure All Disease?

The Biophysicist, the Billionaire, and the Quest to Cure Disease—an Update Mark Zuckerberg & Priscilla Chan tapped Stanford's Steve Quake to help eradicate disease by 2100.—a progress report in year 8 of The Chan Zuckeberg initiative, By David Ewing Duncan.

Q&A: Steve Quake, PhD, Head Scientist of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative; Professor of Bioengineering and Professor of Applied Physics at Stanford University.

Comments by Priscilla Chan, MD, speaking at Cure in New York City,

Whitepaper: The Future of Health. A report I executive edited and wrote part of; produced by Attention Span Media, sponsored by the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB. 11 topics from cancer, the brain, and bionics to climate health and the patient experience.

Podcast from my archives: Online Personas: Defining the Self in a Virtual World, Commonwealth Club of California, November 30, 2006—I moderated a panel that includes 22 year-old Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook plus Reid Hoffman of LinkedIn, Shawn Gold of Second Life, and Robin Harper of MySpace. In 2006 only 40m people were on social media.

__________

FUTURES is a column and a newsletter about possible futures at a pivotable moment in history, where the future could turn out wondrous—or not. I’m asking the most interesting people I can find what they are most excited about and most afraid of for the future, and why.

Help Support Futures! If you like the column, join as a paid subscriber for a tiny amount.

For more stuff check out my website: www.davidewingduncan.com

__________

New Essay

Zuckerberg and Chan on stage in 2016 when they announced the launch of their initiative.

The Biophysicist, the Billionaire, and the Quest to Cure Disease—an Update

Mark Zuckerberg & Priscilla Chan tapped Stanford's Steve Quake to help eradicate disease by 2100.—a progress report in year 8 of The Chan Zuckeberg initiative.

By David Ewing Duncan—September 18, 2024

On a sunny San Francisco September afternoon in 2016, I watched Mark Zuckerberg announce with his wife, Priscilla Chan, that they were pledging 99% of Zuckerberg’s then $43 billion fortune to cure all disease by 2001. Like most people in the audience I tried not to smile at this decidedly Quixotic ambition, a reaction that was somewhat tempered when C&Z added that they were entrusting their quest to a bevy of of highly respected scientists like the Stanford biophysicist Steve Quake, a star researcher not known for tilting at windmills.

When I sat down recently to chat with Quake—at the Lake Nona Impact Forum in Orlando—he told me his first reaction to the CZI plan: that it was ridiculous. But he came around when Zuckerberg and Chan explained that the aim was aspirational, a Very Big Idea intended to inspire—and that the meta couple would be closely adhering to real science. “They convinced me,” said Quake, “and they have stuck to what they promised.”

I first met Steve Quake in the Bay Area of the early 2000s, when I was covering the early days of biotech merging with biophysics, bioengineering, and advanced computing. He was one of a small cadre of brilliant young scientists making names for themselves with highly original thinking and discoveries in rapidly emerging fields like microfluidics, genomics and other omics, and single-cell expression—and more recently with how to characterize, analyze, and bioengineer cells, including immune cells. Not only did I go back to Quake many times for quotes, I also found him to be thoughtful and down to earth on a broad array of topics, including some ranging far beyond science.

Since 2016, Zuckerberg and Chan have spent around $6.4 billion on a range of projects, including big efforts to research and better understand COVID-19 and infectious disease, and to build a “cell atlas,” collaborating with other research centers to redefine how we understand these fundamental units of life. The couple has invested in new technologies like advanced cryo electron microscopy, creating the Chan Zuckerberg Institute for Advanced Biological Imaging in Redwood City, California, with plans to spend up to $900 million to support it.

CZI is betting big on AI, too, mirroring Meta’s substantial investment. At Harvard they recently launched the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence–named after Zuckerberg’s mother, Karen Kempner Zuckerberg—pledging $500 million to support it for 10 to 15 years.

Emulating the Silicon Valley ethos of bashing the old and building the new, CZI also has devoted itself to busting up orthodoxies in how scientists’ approach and organize biomedical research. “We wanted to be interdisciplinary,” said Priscilla Chan, in a recent interview on stage at Cure in New York City. “We wanted to bring people from all different backgrounds to work on a shared problem, to work across sectors to solve a collaborative problem together, something that wouldn't have been possible within a single lab.” For more of this interview with Priscilla Chan, see additional excerpts below.

But will all of this be enough to truly end all disease by 2100? Uh, no. We still barely understand disease and the workings of the human body today despite extraordinary progress over the past 100 to 200 years, and it’s hard to imagine we’ll know everything in a mere 76 years—something Steve Quake talks about in his interview below.

What’s more likely (I hope) is that CZI and other out of the box initiatives will help to overthrow old and worn out and frankly unhelpful paradigms of how we approach biomedical research. This starts with reducing or eliminating the prevalence of Principle Investigators, as Priscilla Chan suggests—the “Lone Genius” model that’s straight out of the Renaissance (think Leonardo da Vinci), where great leaps forward too often come from ivory tower superstars running their own individual shows and deciding, often in a small-science way, what problems to solve. What’s needed is a more coordinated and collaborative enterprise that connect and criss-cross disciplines.

I need to mention that CZI’s accomplishments come at a time when Mark Zuckerberg and Meta have been facing fresh rounds of criticism and lawsuits over evidence showing an alarming rise in social media addiction and negative mental health outcomes in young people. This week, Instagram announced new restrictions for what information children can access, but critics say it isn’t enough. It’s worth noting that Meta stock is the source of CZI’s funding—with Zuckerberg’s fortune now worth $173 billion. He also is the very visible face of of both enterprises. I checked CZI’s website for projects researching the impact of social media on users’ gray matter, and didn’t find anything. Entering “social media” into the site’s search engine yielded zero responses, seemingly an oversight for an organization wanting to cure all diseases by the year 2100.

Below is my conversation with Steve Quake, head of science at CZI, when we sat down in a conference room during the Lake Nona Impact Forum last spring.

________

Q&A: Steve Quake, PhD

Professor of Bioengineering and Professor of Applied Physics at Stanford University; Head Scientist for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

First, I asked Quake the question I’m asking everyone for this column on possible futures.

David Ewing Duncan. What are you most excited about and most afraid of for the future, and why?

Steve Quake. I'll start with what I'm afraid of. I'm afraid of the retreat from reason, logic, scholarship, and truth in the world today. Someone told me the other day that I’m working in the end times of truth. That worries me a lot. My whole life as an intellectual and scientist is predicated on being able to reason, and to depend on a respect for rationality, logic, data, scholarship. And that's becoming a much smaller part of our culture, not just the world in general, but in how decisions are made in important places like the government. And I’m just afraid for what that holds for us in the future.

Do you think that that this is profoundly different than it has been previously in your lifetime?

Absolutely. And along with that, a loss of confidence in institutions.

What are you excited about?

I'm excited that I'm working for what could be the most important philanthropy ever, and working over the last eight years with Mark and Priscilla. They've committed to giving their whole fortune away during their lifetime, and they have many worthy causes in philanthropy, and they've explored a bunch of them, deciding that science is going to be their primary one.

CZI is sending a lot of checks out, right?

We're a worldwide organization. We give grants in some 30 odd different countries and it's a chance to have impact across the whole world of science.

What makes you, a scientist, want to do that?

It’s the opportunity to give something back to the community. When I was coming up as a scientist, my senior colleagues looked out for me and steered opportunities my way. And there's a chance to do something like that on a very large scale.

Do you do much science yourself these days?

Still do a little bit, yeah. My group is smaller than it's ever been. For 20 years I had a pretty big lab. Now it's very small, but I'm still having a ton of fun. It's like oxygen to be able to do a few projects in my own lab.

How do you think Chan Zuckerberg will change things? What will be the impact, say, in 10 years?

We could ask what is the role of philanthropy in science. Because as massive as the resources are at CZI, we're tiny compared to the NIH, with an annual budget of less than 1% of what they have. I think we've committed around $6.4 billion towards science since the start in 2016. I’d say we're a little larger than the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in both endowment and budget, and a little smaller than The Wellcome Trust in terms of dollars.

You're doing your work a little bit differently than some of these other philanthropies.

That's right. We are doing it quite differently, especially compared to a government program like the NIH. As a private philanthropy we can be very nimble and take a lot of risk. And those are the two things that we try to do. Historically, in our short history, the first big risk was on funding work making human cell atlases. And we were the first funder in there.

A very exciting project, tell me more.

That paid off. A huge success. Now we're maintaining a database with more than 50 million cell profiles. And it's shared with the whole scientific community to use. Many other funders have come into the space. We sort of went and de-risked it and showed that there was good science to be done there and opened it up for the rest of the funding world. And that's what the philanthropy does well. Right now, we see a similar opportunity in artificial intelligence, and we're making a very big commitment there. We're building the world's largest supercomputer for non-profit basic science research. And we’re going to use it around problems of trying to build models, what what we call the virtual cell.

It's kind of our north star, understanding the mysteries of the cell and how cells interact in systems. 20, 30 years ago, the north star would've been understanding the mysteries of the macromolecule. But the genome was sequenced, protein structures were solved, and molecules are very well known now. So the question is, how do they work together in that smallest indivisible unit of life, which is the cell?

And you’re working on reengineering cells, too?

Yeah. Our New York Biohub is aimed at re-engineering cell function in really profound ways to build cellular endoscopes and things like that. Our Seattle Hub for Synthetic Biology [a collaboration with the Allen Institute and the University of Washington] is aimed at engineering cells to build memories and store memories.

Are these biological memories or real memories?

They are like writing events into DNA, into the genome of the cell. Real memories, that's a whole other story that I'm working on in my lab. Our paper just came out in Nature a couple of weeks ago.*

Thinking about the near future, where is this going? Will you be using what you’ve learned about cells to treat humans, or is it still basic research?

We're already seeing things spin out from the research we've done. So even though we're focused on basic science now, we're starting to see the validation that comes out of basic science discovery that you see in clinical applications. Out of the San Francisco biohub, we've seen multiple startups come out. We have diagnostics being used in the clinic. For example, the work we did on making a liquid biopsy for preeclampsia and preterm birth is basic research. Now, the company that licensed that research is just finishing it's 10,000-women clinical trial, the largest ever such trial on a population like that.

What is the name of that company?

Mirvie. If it turns out well, which we'll know in the next few months, they'll have a real test out there, hopefully saving lives this year. Another company we've spun out is trying to cure food allergies with biologics. They should be in its first human trial by the end of this year.

How did this all get started?

We have this a hundred-year mission to cure, manage, prevent all human disease, which on the face of it sounds ridiculous. And I couldn't even say it with a straight face with Mark and Priscilla at the beginning. Scientists aren’t used to thinking on a hundred-year timescales. But it’s not just our work, it's something we’re working to get the whole scientific community rallied around.

I wonder what people would have thought a hundred years ago about a goal like yours in their future?

A hundred years ago, mortality in the United States was twice as high as it is now. And if you look at what the causes of mortality were in, say, 1900 versus now, we have largely eliminated infectious disease in the US. 100 years later, which is now, the two biggest chunks of mortality are heart disease and cancer. And so, you might say we should just be focused on heart disease and cancer. But mortality doesn't tell the whole story. There's a very interesting study on the most transformative medicines approved by the FDA since the 1980s. There's like two dozen of them. And these are incredibly important. For almost all of them, it traced back to basic science discovery 30 years earlier.

Since this column is about the future, where do you want to be in a hundred years? Will all disease really be cured?

It is so hard to think on a hundred-year timescale, but I hope that we will see a completely different way of taking care of human health in 100 years. There'll be completely new kinds of medicines. Right now, we have small molecules, biologics. I think cells as a medicine will be routine. I think many things that are treated with chronic medicine now, hopefully we will treat them with single, one-shot approaches in one form or another. And so, within this narrow lens of human health that I'm obsessed with right now, it'll be very different.

This gets back to your greatest fear—will things be better?

It's not a given we'll be in a better place in a hundred years given the erosion of trust in science and all the rest.

Are you feeling that yourself? In your work, are you feeling like you have to look over your shoulder a little bit more?

No. My world is lovely. I live in a world where we are thinking about all these things, what could go wrong, but the world of decision making and at the national government level—not just in our country, but other ones—this feels less of a priority. And this is not just in science. You probably saw an article in The New York Times the other day about constitutional law professors. They're all really upset and discouraged now. Right? They can't justify what they're teaching their classes. That's like the microcosm of my fear, that sort of thing

Comments by Priscilla Chan, MD

Priscilla Chan speaking last May at the appropriately named Cure in New York City.

These comments are excerpts from an interview with Priscilla Chan at Cure in New York. A joint production of Cure—where I am Creative Director—and the New York Academy of Sciences, Dr. Chan was interviewed by Richard Lifton, PhD, President of Rockefeller University, home of the CZI Biohub in New York.

Richard Lifton: So how have you been thinking about the role of the Biohub initiative… how are you thinking about this going forward?

Priscilla Chan: So we started the first biohub in San Francisco in 2016, and it was sort of founded on some principles—like we wanted to be interdisciplinary, we wanted to bring people from all different backgrounds to work on a shared problem… And we knew we had to build off and partner with great universities because universities are where so much interesting and incredible talent comes from. And so we were in the Bay area, so we partnered with Stanford, UCSF and uc, Berkeley and what we were hoping for actually happened, great talent decided to, Steve Quake and Joe DeRisi are founding co-presidents.

They set out working on the human cell atlas and incredible breakthrough work in infectious disease. And they drew upon their communities at their partner universities to come in and collaborate from all different angles on the problems that they were working on in San Francisco.

One big scientific question is, can we harness the immune system to actually detect, prevent and treat disease? …Can we give immune cells special jobs and teach them how to record specific signals when they've seen something we want to know about within the body? And you can imagine how that would be useful for hard to detect diseases like ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancers that are in very protected spaces within your body or neurodegenerative diseases. The brain and the central nervous system are isolated and very hard to penetrate…

An immune cell can go learn something, detect whether or not there's a signal for say ovarian cancer. And I imagine it will then record that information and then maybe just break down and release its parts into your bloodstream and then we can do a simple blood test to look for that signal. Pretty cool. But if… we can engineer an immune cell to go to a specific target destination and do something, deliver something, take an action, kill something.

Richard Lifton: …what do you see for the next 10 years?

Priscilla Chan: Looking forward, I want to make sure that we're continuing to be really sharp about are we taking on the right projects that fit us as an organization, big projects team-based science that's a good fit for us. We want to make sure that we're incentivizing people with new skill sets, new points of view to enter into the spaces that we care about… We want to work on projects that improve both the science and the speed at which science is happening. We are builders.

The entire interview can be viewed here.

_________

White Paper

The Future of Health Summit in Boston earlier this year, which included my talk about how the report highlights two possible futures in healthcare—one where we effectively and equitably utilize new technologies and reform issues of policy, payment and access—and one where we don’t.

I executive edited and wrote part of this report produced by Attention Span Media and sponsored by the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB. The report addresses 11 topics from cancer, the brain, and bionics to climate health and the patient experience.

Download_________

Podcast

Mark Zuckerberg in 2006.

Online Personas: Defining the Self in a Virtual World

Commonwealth Club of California, November 30, 2006—Moderated by David Ewing Duncan

Panel: Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook; Reid Hoffman, LinkedIn; Shawn Gold, Second Life ; Robin Harper, MySpace

This discussion about the implication of social media on the self occurred when around 40 million people were on these sites—compared to 5.17 billion today. In 2006, MySpace was the social media king, ranking #1 in social media traffic at the time, and was the 4th most visited site on the total World Wide Web. Facebook was the #7 most visited social site.

XXXXX