Larry Brilliant: A Cassandra for Our Times

He helped eradicate smallpox, but his pandemic warnings were ignored. Now he's worried about an emerging contagion of anti-science. Also from my archives: "Coronavirus Cassandras" (Vanity Fair), more

In this issue of FUTURES

Theme: The Augur of Epidemiology

New Essay:

· Larry Brilliant: A Cassandra for Our Times: He helped eradicate smallpox, but his pandemic warnings were ignored. Now he's worried about an emerging contagion of anti-science, by David Ewing Duncan.

Q&A

Larry Brilliant’s hopes and fears for the future

From my Archives:

“Prepare, Prepare, Prepare”: Why Didn’t the World Listen to the Coronavirus Cassandras? People (Larry Brilliant, Bill and Melinda Gates, the World Health Organization) have been shouting about “Disease X” for decades. But talk and action were on different planets, by David Ewing Duncan, Vanity Fair, March 27, 2020

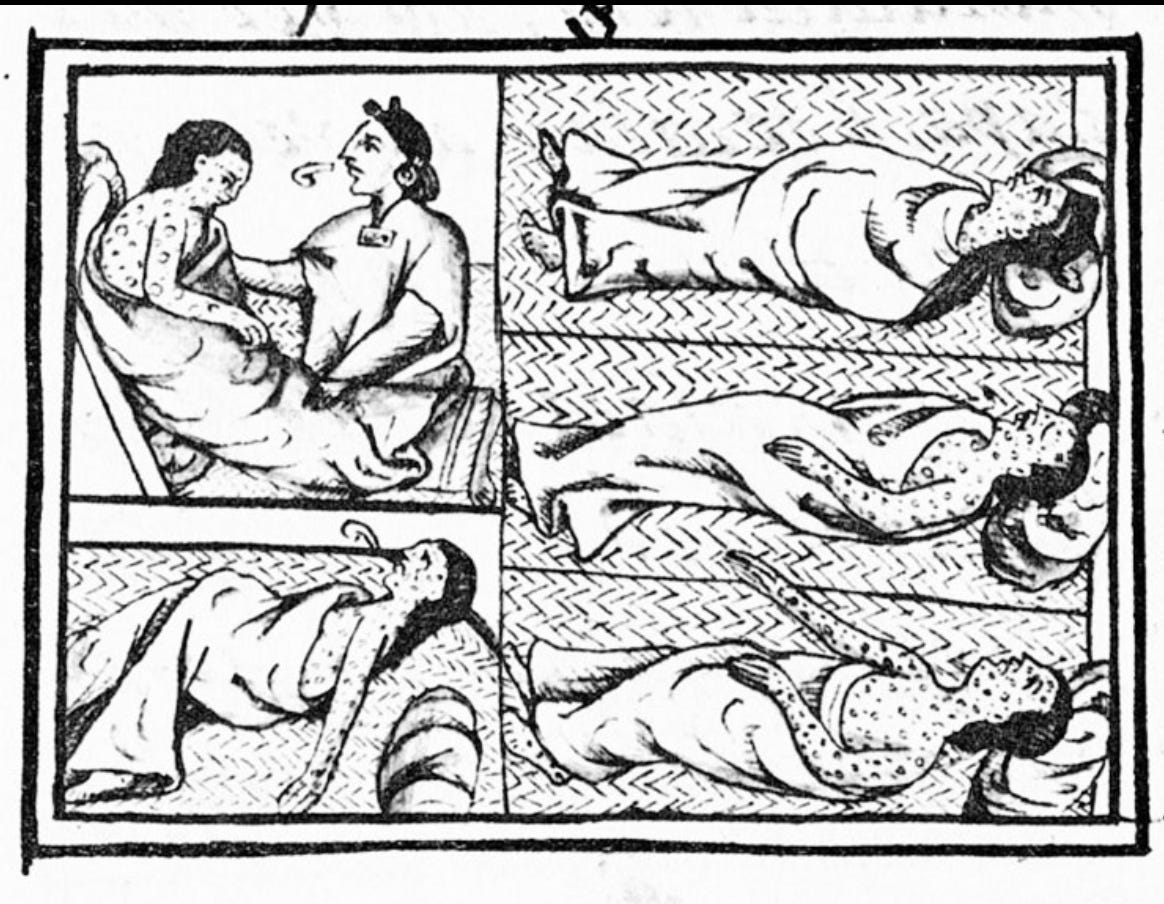

History: Smallpox in the conquest of the Americas: more deadly than gunpowder or steel, excerpts from my book: Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas (“an admirable tour de force,” NY Times), Crown, 1996

After the Madness—Pandemic Silver Linings in Bioscience: Will the frenzied rush to understand and treat SARS-CoV-2 bring longer lasting benefit to the world of scientific research and medicine? by David Ewing Duncan, PROTO.LIFE, June 4, 2020

Cassandra image above: Palmer, Henrietta L., The Stratford Gallery, 1859, New York, D. Appleton and co.

__________

FUTURES is a column and a newsletter about possible futures at a pivotable moment in history, where the future could turn out wondrous—or not. I’m asking the most interesting people I can find what they are most excited about and most afraid of for the future, and why.

Help Support Futures! If you like the column, join as a paid subscriber for a tiny amount.

For more stuff check out my website: www.davidewingduncan.com

__________

New Essay

Larry Brilliant: A Cassandra for Our Times

He helped eradicate smallpox, but his pandemic warnings were ignored. Now he's worried about an emerging contagion of anti-science.

By David Ewing Duncan—May 10, 2025

“The arc of history will not bend towards justice without you bending it. Public health needs you to ensure health for all. Seize that history. Bend that arc. I want you to leap up, to jump up and grab that arc of history with both hands, and yank it down, twist it, and bend it. Bend it towards fairness, bend it towards better health for all, bend it towards justice!”

- Larry Brilliant, Commencement Address, Harvard School of Public Health, 2013

Larry Brilliant is a troublemaker. At age 81, he retains a mischievous, Puck-like gleam in his eye that makes you wonder what he’s up to now. A seeker and a doer who embraces life as it presents itself, Brilliant is a physician, epidemiologist, inventor, organizer, and provocateur best known for being part of the World Health Organization team in the 1970s that eradicated smallpox, a terrible plague that he says killed at least half-a-billion people over the centuries.

His serendipitous life has taken him from his hometown of Detroit, Michigan and medical school at Wayne State University to Alcatraz, where in 1969 he became the physician to native American protesters who took over the island for 19 months to draw attention to the plight of their people. Soon after he appeared in the documentary film Medicine Ball Caravan about a hippy caravan that included the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Joni Mitchell, and their tour of the American hinterlands to spread the gospel of flower power.

Heading next to South Asia, Brilliant joined an ashram and met the Hindu sage Neem Karoli Baba, who gave Brilliant the name Subramanyum, meaning “pure, clear, and fresh.” Neem Karoli Baba also advised Brilliant to join the effort to eliminate smallpox, suggesting to the young physician that one way to counter injustice is to try to help those least able to help themselves—an admonition Brilliant took to heart and still practices. That led him to be present in Bangladesh in 1975 when the last known victim of smallpox was treated and saved—a 2-year-old girl named Rahima Banu. “I remember when the scabs fell off and that was it,” said Brilliant.

Also in the 1970s, Brilliant co-founded the Seva Foundation, an international, non-profit, health foundation that has reached out to 64 million people in underserved areas of the world to provide eye glasses, optical services, and sight-saving surgeries. In 1985 Brilliant cofounded with Stewart Brand The Well, the legendary precursor to most things Internet, and in 2005 he became the first Executive Director of Google.org, Google’s nonprofit.

In the early 2000s, Larry Brilliant became increasingly worried about a pandemic that could happen anytime and the lack of preparation or even concern in the government. In 2006, he was awarded a $100,000 TED prize that he used to help “…build a powerful new early warning system to protect our world from some of its worst nightmares."After the H1N1 swine flu outbreak , Brilliant and several friends and colleagues helped create and advise on the film Contagion, released in 2011.

In March of 2020, I wrote a story for Vanity Fair about Brilliant and a few other prominent voices that had been warning a pandemic was inevitable, but were largely ignored. Brilliant’s prophetic insistence and the curse of not being believed reminded me of Cassandra, a princess of Troy in the Illiad who was given the gift of knowing the future by the gods but was not believed. The story from my archives is below, after my Q&A with Larry Brilliant.

I also have included in this issue of Futures an excerpt from my biography of Hernando de Soto, the conquistador who explored and ravaged territories from Peru to the Carolinas. (Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas, Crown, 1996). The excerpt is a brief, eye-witness account of the horror of a smallpox pandemic that was brought to the new world by the Europeans and proved more deadly than bullets and swords. Finally, I’ve included a more positive article I wrote in 2020 for Proto.Life about a few silver linings that were even then emerging from the ravages of the pandemic.

A few weeks ago, Brilliant spoke at NextMed in San Diego and offered some thoughts on what people can do to counter the rising contagion of anti-science and disinformation. Never one to mince words, Brilliant addressed the current age of disinformation about science that we are now living through, telling the audience:

“To counter disinformation in a compassionate way we have to get good information out there. You were given a broken and beautiful world. You will take this world in your hands and make it less broken and more. Find something good to do. Doesn't have to be big and messianic. Help somebody who's in worse shape than you…”

The video of his talk and Q&A with NextMed co-host Shawna Butler is here.

In the end, Larry Brilliant—now CEO of the Skoll Global Threats Fund and also CEO of an AI and health start-up named Evity Technologies—remains optimistic about the future. He points out that the world has been in deep trouble before—for instance, with Smallpox—and we were able to overcome it. “I believe we can get through this,” he said. Take a peek below to find out how.

________

Q&A: Larry Brilliant

I recently ran into Larry Brilliant first at NextMed in San Diego and then a few days later at TED in Vancouver. As always, I first asked him the question that I ask everyone for this column about possible futures.

David Ewing Duncan. What are you most excited about and most afraid of for the future, and why?

Larry Brilliant: what I'm most excited about is what Arthur Clark famously said—that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. We have two technologies like this right now. People say AI is indistinguishable from magic, but it's also true of medical science. I encourage anybody who doubts that to read Venki Ramakrishnan’s book called Why We Die. He won the Nobel Prize for chemistry for unpacking the role of the ribosomes, the little factories inside cells that make proteins. What he's done is shown you the dance, the choreography of all the cells, the immune system, and how life itself hangs in the balance. When I went to medical school, we didn't even know these existed. So medical science has now come in with this magic.

What does this age of magic in medicine mean for people?

All of these discoveries are a big deal because when we start talking about longevity and healthy longevity, there's a lot of snake oil out there, but we can actually begin to unpack the science of it. My hope is that we can not only extend life but extend years of health. If you only extend longevity, then you are going to wind up with a messed up demographic triangle and dependency ratio. And unfortunately, you'll be a static country like Japan, which doesn't have the energy to have innovation. There are so many things good that could happen to us as we learn the fundamental biology of life.

What are you most afraid of?

Well, you can't not be afraid of the careless and haphazard way in which the United States government is endangering almost a century of how countries work together. Like the prime minister of New Zealand said: “this is not how friends behave.”

What about the US pulling out of the World Health Organization, the group you worked with to eradicate smallpox?

There are lots of reasons why we should be part of the World Health Organization from a strategic financial stand point, and also from a national security perspective, and of course because it’s saving people’s lives. I'm not sure that not being part of the WHO with actually happen, it takes a year to formally leave. I’m not even sure what it means to leave WHO since so many of the relationships between people are informal.

So what’s to be done?

What makes me optimistic even in these troubled times, when there's capriciousness and danger, is that we might out of this find something that we could all do together. I think healthy longevity is something that all of us want. We can give in to the snake oil, or we can get to the pure science of it and really unpack that. We can talk about what we’re learning about the fundamental blueprint of life, the way diseases work, how much we're learning, how great the science is, because it's indistinguishable from magic. It really is.

But many scientists and people who respect science are feeling… what? Numb right now? Very worried?

I remember a moment when things were even worse than now, when the US had 28,000 nuclear weapons pointed at the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union had 23,000 or so pointed at us. Because of that deficit Russia began to try to create a chimera, a virus that was half smallpox and half Ebola with a five-year billion dollar plan that Mikhail Gorbachev signed onto to create a bioweapon that could kill a 100 million Americans. As bad as it is today that was worse. But at the same time, we got together, Russians and Americans and doctors from 20 other countries to eradicate smallpox, and it couldn't have happened without the Russians. It was a Russian idea really. Professor Viktor Zhdanov, the Russian Deputy Minister of Health and the Soviet representative to WHO, he came up with the idea—why don't we all work together on this one disease, smallpox? And we did, and I was the youngest person on that WHO team that eradicated this disease in the seventies.

What was that like?

I got to see the last case of smallpox in the wild. I saw this little girl named Rahima Banu, a 2-year-old girl, on Bhola Island in Bangladesh [in 1975], when the scabs fell off and that was it, that was the end of an unbroken chain of transmission that killed 500 million over the centuries.

But how do we persuade people to follow the science?

What troubles me the most right now is the alternative facts out there. I mean, it's denying the whole history of Western civilization and trying to restructure it. This myth is toxic.

Ignoring science when our civilization is based on science could turn out badly.

The thing about nature is it doesn't care whether you believe in it or not. The thing about science is you can deny it only so long, and then you reap the whirlwind of disease and death. And it's not that anybody does it to you, it's just that it's there. If you want to live a longer, healthier life, if you want your kids to be healthy. and if you deny science, then you're denying not only the history of what medical science has done to save so many lives, but you're denying your children a chance to live a healthy, longer lifespan and beyond. I'm hoping that there's a self-correcting mechanism in here when people all over the country start realizing that their 401Ks are now 101Ks. Then they will have zero Ks. And then maybe they’ll realize there’s something wrong with this idea of tariffs.

Why do you think people deny science? It's all around them, it’s why a car goes when you press on the accelerator, or a light goes on when you flip a switch.

Part of it is how scientists communicate. Some are terrible at communicating, and some are difficult to put up with because they are full of themselves. They act like they are experts and know more than other people and, even if they do, they shouldn’t talk down to people. I remember going before the board of directors at the Skoll Foundation and trying to explain to them how we can stop pandemics but not stop outbreaks. Paul Farmer [the Harvard physician and global health advocate] used to love to quote me that outbreaks are inevitable, but pandemics are optional. But even to say something like that I need to explain it, that outbreaks only mean a few cases, and it's our option to find them, and to react to them quickly. If we don’t that, the outbreak could become a pandemic. The arrogance and the way we talk to people sometimes is not a good thing.

One issue that seems to be a failure of communication is the inclination of some experts to talk as if the science of, say, a pandemic is certain when in fact it’s not. It’s the nature of scientific inquiry to be discovering new information that could change what was previously thought. I wonder if the experts during the pandemic had more often admitted this, more people would trust experts today.

The same thing is true about AI. What we know about it right now is very different than what we will know about it tomorrow. I believe that science is a verb, not a noun. I think that the hardest thing to communicate is the scientific method is very happy when you make a mistake because you can improve our understanding of it. It’s an ongoing process. But to say that is not normal—or to be looking for mistakes. It’s hard for some experts to admit this when people want answers.

But scientists build entire careers on wanting to be right.

I remember when I went to the University of Michigan and became an assistant professor, and I had to give my first lecture. I had diarrhea. I was so frightened. I had to keep excusing myself. But I learned, I guess, that you have to laugh at yourself. Yeah. I mean, we had this sportscaster, he used to always end his broadcast by saying that angels fly because they take themselves lightly. I like that. It's good to take the science, the saving of lives, seriously, but not to take yourself too seriously.

______

From my Archives

Vanity Fair

“Prepare, Prepare, Prepare”: Why Didn’t the World Listen to the Coronavirus Cassandras?

People (Larry Brilliant, Bill and Melinda Gates, the World Health Organization) have been shouting about “Disease X” near constantly for a couple of decades. But talk and action were on different planets,

By David Ewing Duncan, March 27, 2020

Named for the mythical princess of ancient Troy who prophesied her city’s downfall but wasn’t believed, the “Cassandra Complex” is what philosophers call pervasive doubt about a true or obvious prediction. The phrase has been cited in modern times to describe prescient warnings about everything from climate change to stock market crashes that, once upon us, are met with incredulity.

In the age of pandemics, we’re now realizing who the Cassandras were that cautioned us about the coronavirus contagion—prognosticators like famed epidemiologist Larry Brilliant. In 2006, he took the stage at TED to alert the world about the disastrous effects of pathogens run amuck. “The key to preventing or mitigating [a pandemic],” said Brilliant in that talk, “is early detection and rapid response. We will not have a vaccine or adequate supplies of an antiviral… The world as we know it will stop.” He predicted that perhaps a billion people would become infected and over 100 million would die. He also imagined global depression, lost jobs, and a cost to the economy of up to $3 trillion. Sound familiar?

As the belated responses to the COVID-19 outbreak have played out in the U.S. and many other nations, we have seen the Cassandra Complex writ large. Donald Trump has perfectly channeled another character in the drama, King Priam of Troy—the monarch in the Cassandra myth who dismissed her prophecies—by spending weeks dismissing auguries of the pandemic, along with a raft of advisers, pundits, and sycophants who echoed him like a chorus in a Greek tragedy. As we now know, Trump’s dismissal of the threat in the U.S.—calling it an impeachment hoax by the Democrats and so forth—wasted precious time when the government should have been ramping up tests for the virus, sequestering early cases, preparing hospitals, and mobilizing the federal government’s response teams.

Read the rest of this essay here.

Book Excerpt

Smallpox and the Spanish Conquista: More Deadly than Gunpowder or Steel

Excerpt from my book Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas (Crown, 1996), a 750-page biography of Soto and a history of the early conquista of the Americas by the Spanish, a book the NYT’s called “an admirable tour de force.”

Smallpox and the Decimation of the Cofitachequi in the Carolinas, 1540

On May 3, 1540, Hernando de Soto, leading about 500 Spaniards on an expedition of conquest in what is now central South Carolina in the Southeastern United States, marched into the heartland of a kingdom called Cofitachequi. Unknown to many Americans today, the people living here in the first third of the 16th century were part of a civilization called Mississippian that lived in impressive cities and built roads, temples, palaces, and earthen pyramids. Like other Mississippian kingdoms and chiefdoms, the Cofitachequi probably had been influenced by the Aztecs far to the south, whom they traded with.

Eyewitnesses from Soto’s expedition describe the Cofitachequi people as being clothed in colorful leather and cloth tunics, leather breastplates, and toga-like robes—and wearing lots of locally-harvested fresh-water pearls. Their capital, Talimeco, contained temples and palaces built with tall, slopped roofs and decorated with mica and pearls. When Soto and his men on horses appeared out of nowhere, he was greeted by the queen of the Cofitachequi, who told Soto that her domain had recently been decimated by a plague that had killed nearly everyone—probably smallpox caught when locals came into contact with other Spaniards trying to start a colony on the coast.

Excerpts:

The magnificence of the queen and her pearls made the Spaniards immediately put the miseries of the past few days behind them. They also were relieved to find a cacica [ruler] willing to welcome them peacefully and to offer them food and housing—a reception they had not expected after hearing about the Cofitachequi’s warlike reputation. But there was a reason for the queen’s friendliness. As Soto quickly discovered, this great kingdom, the largest and most sophisticated they had seen, had recently suffered a catastrophic plague that had decimated its population, and its ability to raise an army…

Whatever the grandeur that was Cofitachequi, it was all crashing down in 1540 as the Spaniards found themselves marching through a settled country “very pleasant and fertile,” with “excellent fields along the rivers,” but almost entirely emptied of people. “About the town [of Cofitachequi],” recalled Elvas [an eyewitness in Soto’s army],* “within the radius of a league and a half were large, uninhabited towns, choked with vegetation, which looked as if no people had inhabited them for some time.” He also notes that that these eerily empty towns were full of houses filled with “a considerable amount of clothing—blankets made of thread from the bark of trees and feather mantles (white, green, vermillion, and yellow). There were also many deerskins, well colored with designs drawn on them and made into pantaloons, hose, and shoes.” Alonso de Carmona [another eyewitness] later told of seeing “long houses full of bodies who died from the plague that had raged there.”

The queen apologized for the lack of food on hand to provide to the Spaniards, blaming the “pestilence of the year before that had deprived her of provisions…”

*Elvas is an expedition member and chronicler known as “The Gentleman from Elvas,” a knight from Elvas, Portugal. He kept a diary that was later published as: True Relation of the Hardships Suffered by Governor Don Hernando de Soto and Certain Portuguese Gentlemen in the Discovery of the Province of Florida.

And Finally, something more positive from my archives…

PROTO.LIFE

After the Madness—Pandemic Silver Linings in Bioscience:

Will the frenzied rush to understand and treat SARS-CoV-2 bring longer lasting benefit to the world of scientific research and medicine?

by David Ewing Duncan, June 4, 2020

On March 16, a single tweet mobilized an army of over 700 geneticists from 36 countries to battle a tiny virus by trying to understand the role human genetics plays in why some people have no reaction to COVID-19, and others get very sick and die. “Goal: aggregate genetic and clinical information on individuals affected by COVID-19,” tweeted Andrea Ganna, a geneticist at the Institute for Molecular Medicine in Helsinki, Finland. Just a few weeks later the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative was up and running and is now identifying human genes associated with COVID and its symptoms—nothing definitive yet, although the possibility of breakthroughs has been substantially improved by the combined DNA-discovery firepower of over 150 labs and biobanks that store and analyze millions of human genomes.

Nor is this pandemic display of raw scientific muscle and intensity of focus unique right now. Pandemic-bound researchers around the world are combining forces for possibly the largest scientific hive-mind effort in history that’s converging on a single conundrum. It also arrives as a slew of technologies developed over the past generation are coming online and being applied to the COVID puzzle—everything from CRISPR gene editing and faster and cheaper genetic sequencing to social media and the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in bioresearch and health IT.

COVID-19 has ravaged bioscience just like it has cut a destructive and sometimes deadly swath through much of what we used to call “normal.” Yet even as labs have shuttered, experiments have halted, and droves of scientists and technicians have been laid off—and research and clinical attention has been diverted from any disease that’s non-COVID—is it possible that some scientific silver linings may emerge out of this tragic Year of the Pandemic?

Read the rest of the article here.

XXXXX

Good article