As We Vote, do the Rhythms of Life Seem… Off? Can We Restore a Steady Beat?

Politics and the Heart. My essay on how modern life—including politics—impacts our hearts, literally and metaphorically | Plus: “Growing Heart Cells Just for Me" | Video: “Playing Mambo with My Heart"

Illustration by Sara Neuhart for MIT Technology Review

In this issue of FUTURES

Theme: Politics and the Heart

Commentary: Thoughts, anxieties, hopes, and fears on a potential swing day in history—and the ultimate moment for a column called Futures.

New Essay: The arrhythmia of our current age: The rhythms of life seem off. Can we restore a steady beat? MIT Technology Review, By David Ewing Duncan, October 30, 2024

From my archives: “Growing Heart Cells Just for Me: A new method to make stem cells transformed my blood cells into beating heart cells in a petri dish. What this told me about my future risk and potential treatments for disease” by David Ewing Duncan, Technology Review, 2011

Video: Talk at a “Quantified Self” Meet-Up: “Playing Mambo with My Heart,” about getting brand new heart cells made just for me

__________

FUTURES is a column and a newsletter about possible futures at a pivotable moment in history, where the future could turn out wondrous—or not. I’m asking the most interesting people I can find what they are most excited about and most afraid of for the future, and why.

Help Support Futures! If you like the column, join as a paid subscriber for a tiny amount.

For more stuff check out my website: www.davidewingduncan.com

__________

Do you feel it? That slight tightness in the chest where your heart may be missing a beat or two as the news rolls in today—and roils, titters, and surges.

Maybe you’ll feel your jaw clenching this afternoon as the race in North Carolina or Nevada tightens, and then tightens more. Or the spark that usually flashes in your eyes because you’re basically an optimistic person will dim a notch or two with the news from Georgia, and then brighten up again over a shift in the count in Pennsylvania even as polls close and the world and time seem to slow to an excruciating crawl.

Yes, November 5, 2024, has finally arrived. This day that’s been fraught with meaning and dread and guarded excitement for months and months and months, whatever issue you’re worried about—inflation, women’s reproductive rights, war in the Middle East or Ukraine, immigration, social justice, taxes, childcare, climate change, access to healthcare, belief in science and facts—or democracy itself.

Do you feel it? That steady beat of your heart quickening, the anxiety building?

Below I’ve excerpted my essay just out about the arrythmia of our times, the sense that rhythms are off in society, on our planet. It starts with my own sudden and unexpected arrhythmia and out of control pulse rate, a scary moment in 2022 when my heart literally lost its steady cadence after a bout with Covid. But the essay isn’t really about me or the muscle that pumps blood through 60,000 miles of veins, arteries, and capillaries inside me to fingertips, toe tips, frontal cortex, kidneys, clenched jaws, and eyes that sparkle.

It’s much more about the wonders of modern life, but also the anxieties we face in the 2020s—including elections and politics that set us on edge. It’s about a remarkable species—us—that can be ingenious, creative and noble and come up with solutions to solve many of our problems, but also can be shallow, selfish, ridiculous, and so driven by fear that we fail to act to fix challenges, perils and quandaries that are fixable.

This dichotomy in human nature is the essence of this column that is about possible futures that could be wonderful, or not.

We can’t know the future or what will actually happen even five minutes from now—or, say, this evening as election returns come rolling in. But we can do our best to optimize what’s to come. That’s the point of voting, of democracy, of us collectively deciding as much possible what our future will be—while hoping with all our might that our better angels prevail.

Do you feel it?

_______

New Essay: MIT Technology Review

Below are two excerpts from my just published essay in Technology Review about the approaching election and the strange mix of anxiety and guarded optimism that I’m feeling right now—how about you?

For the complete essay, click here.

The arrhythmia of our current age

The rhythms of life seem off. Can we restore a steady beat?

By David Ewing Duncan, October 30, 2024

thumpa-thumpa, thumpa-thumpa, bump,

thumpa, skip,

thumpa-thump, pause …

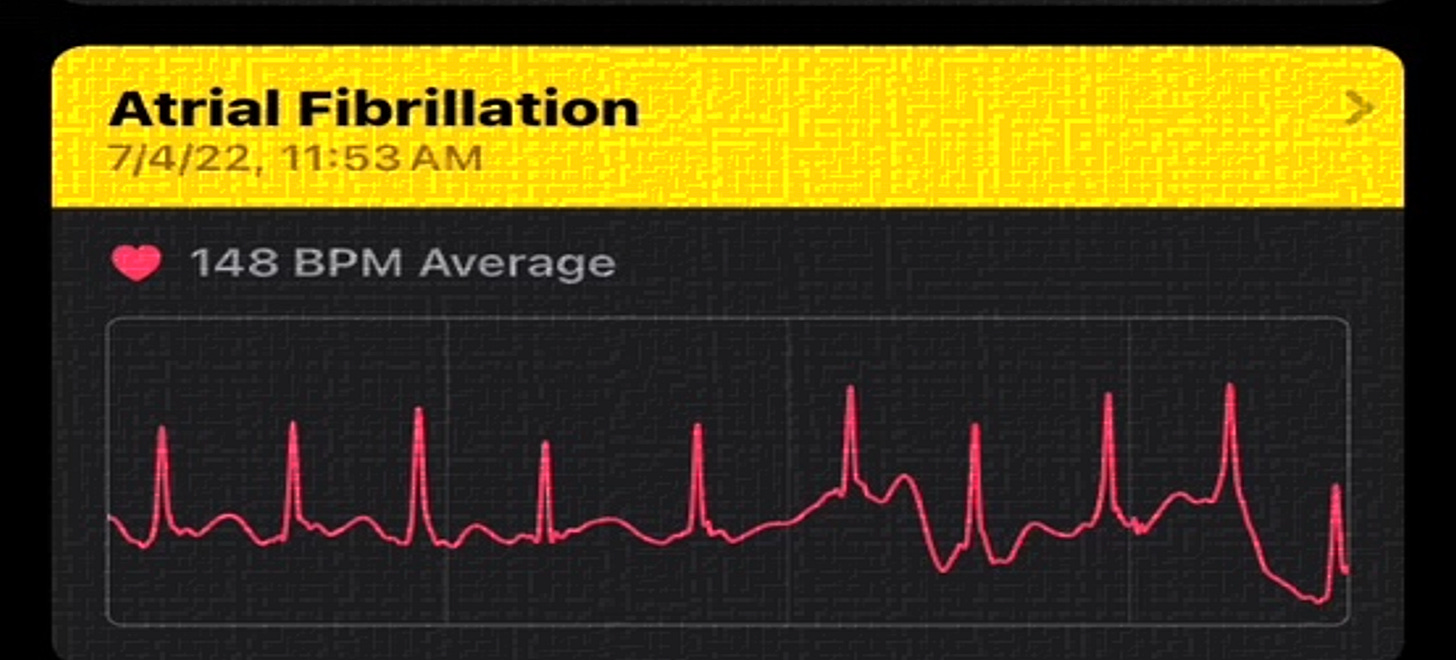

My heart wasn’t supposed to be beating like this. Way too fast, with bumps, pauses, and skips. On my smart watch, my pulse was topping out at 210 beats per minute and jumping every which way as my chest tightened. Was I having a heart attack?

The day was July 4, 2022, and I was on a 12-mile bike ride on Martha’s Vineyard. I had just pedaled past Inkwell Beach, where swimmers sunbathed under colorful umbrellas, and into a hot, damp headwind blowing off the sea. That’s when I first sensed a tugging in my chest. My legs went wobbly. My head started to spin. I pulled over, checked my watch, and discovered that I was experiencing atrial fibrillation—a fancy name for a type of arrhythmia. The heart beats, but not in the proper time. Atria are the upper chambers of the heart; fibrillation means an attack of “uncoordinated electrical activity.”

I recount this story less to describe a frightening moment for me personally than to consider the idea of arrhythmia—a critical rhythm of life suddenly going rogue and unpredictable, triggered by … what? That July afternoon was steamy and over 90 °F, but how many times had I biked in heat far worse? I had recently recovered from a not-so-bad bout of covid—my second. Plus, at age 64, I wasn’t a kid anymore, even if I didn’t always act accordingly.

Whatever the proximal cause, what was really gripping me on July 4, 2022, was the idea of arrhythmia as metaphor. That a pulse once seemingly so steady was now less sure, and how this wobbliness might be extrapolated into a broader sense of life in the 2020s. I know it’s quite a leap from one man’s abnormal ticker to the current state of an entire species and era, but that’s where my mind went as I was taken to the emergency department at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital.

Maybe you feel it, too—that the world seems to have skipped more than a beat or two as demagogues rant and democracy shudders, hurricanes rage, glaciers dissolve, and sunsets turn a deeper orange as fires spew acrid smoke into the sky, and into our lungs. We can’t stop watching tiny screens where influencers pitch products we don’t need alongside news about senseless wars that destroy, murder, and maim tens-of-thousands. Poverty remains intractable for billions. So does loneliness and a rising crisis in mental health even as we fret over whether AI is going to save us or turn us into pets; and on and on.

For most of my life, I’ve leaned into optimism, confident that things will work out in the end. But as a nurse admitted me and attached ECG leads to my chest, I felt a wave of doubt about the future. Lying on a gurney, I watched my pulse jump up and down on a monitor, erratically and still way too fast, as another nurse poked a needle into my hand to deliver an IV bag of saline that would hydrate my blood vessels. Soon after, a young, earnest doctor came in to examine me, and I heard the word uttered for the first time.

“You are having an arrhythmia,” he said.

Even with my heart beating rat-a-tat-tat, I couldn’t help myself. Intrigued by the word, which I had heard before but had never really heard, I pulled out the phone that is always at my side and looked it up.

ar·rhyth·mi·a

Noun: “a condition in which the heart beats with an irregular or abnormal rhythm.” Greek a-, “without,” and rhuthmos, “rhythm.”

I lay back and closed my eyes and let this Greek origin of the word roll around in my mind as I repeated it several times—rhuthmos, rhuthmos, rhuthmos.

Rhythm, rhythm, rhythm …

I tapped my finger to follow the beat of my heart, but of course I couldn’t, because my heart wasn’t beating in the steady and predictable manner that my finger could easily have followed before July 4, 2022. After all, my heart was built to tap out in a rhythm, a rhuthmos—not an arhuthmos.

Later I discovered that the Greek rhuthmos, ῥυθμός, like the English rhythm, refers not only to heartbeats but to any steady motion, symmetry, or movement…

In modern times, cardiologists have used rhuthmos to refer to the physical beating of the muscle in our chests that mixes oxygen and blood and pumps it through 60,000 miles of veins, arteries, and capillaries to fingertips, toe tips, frontal cortex, kidneys, eyes, everywhere. In 2006, the journal Rhythmos launched as a quarterly medical publication that focuses on cardiac electrophysiology. This subspecialty of cardiology involves the electrical signals animating the heart with pulses that keep it beating steadily—or, for me in the summer of 2022, not.

The question remained: Why…?

Excerpt 2: Anxiety and Optimism

…the wider arhuthmos some of us are feeling now began long before the novel coronavirus shut down ordinary life in March 2020. Statistics tell us that anxiety, stress, depression, and general mental unhealthiness have been steadily ticking up for years. This seems to suggest that something bigger has been going on for some time—a collective angst that seems to point to the darker side of modern life itself.

Don’t get me wrong. Modern life has provided us with spectacular benefits—Manhattan, Boeing 787 Dreamliners, IMAX films, cappuccinos, and switches and dials on our walls that instantly illuminate or heat a room. Unlike our ancestors, most of us no longer need to fret about when we will eat next or whether we’ll find a safe place to sleep, or worry that a saber-toothed tiger will eat us. Nor do we need to experience an A-fib attack without help from an eager and highly trained young doctor, an emergency department, and an IV to pump hydration into our veins.

But there have been trade-offs. New anxieties and threats have emerged to make us feel uneasy and arrhythmic. These start with an uneven access to things like emergency departments, eager young doctors, shelter, and food—which can add to anxiety not only for those without them but also for anyone who finds this situation unacceptable. Even being on the edge of need can make the heart gambol about.

Consider, too, the basic design features of modern life, which tend toward straight lines—verticals and horizontals. This comes from an instinct we have to tidy up and organize things, and from the fact that verticals and horizontals in architecture are stable and functional.

All this straightness, however, doesn’t always sit well with brains that evolved to see patterns and shapes in the natural world, which isn’t horizontal and vertical. Our ancestors looked out over vistas of trees and savannas and mountains that were not made from straight lines. Crooked lines, a bending tree, the fuzzy contour of a grassy vista, a horizon that bobs and weaves—these feel right to our primordial brains. We are comforted by the curve of a robin’s breast and the puffs and streaks and billows of clouds high in the sky, the soft earth under our feet when we walk.

Not to overly romanticize nature, which can be violent, unforgiving, and deadly. Devastating storms and those predators with sharp teeth were a major reason why our forebears lived in trees and caves and built stout huts surrounded by walls. Homo sapiens also evolved something crucial to our survival—optimism that they would survive and prevail. This has been a powerful tool—one of the reasons we are able to forge ahead, forget the horrors of pandemics and plagues, build better huts, and learn to make cappuccinos on demand.

As one of the great optimists of our day, Kevin Kelly, has said: “Over the long term, the future is decided by optimists.”

But is everything really okay in this future that our ancestors built for us? Is the optimism that’s hardwired into us and so important for survival and the rise of civilization one reason for the general anxiety we’re feeling in a future that has in some crucial ways turned out less ideal than those who constructed it had hoped?

At the very least, modern life seems to be downplaying elements that are as critical to our feelings of safety as sturdy walls, standing armies, and clean ECGs—and truly more crucial to our feelings of happiness and prosperity than owning two cars or showing off the latest swimwear on Miami Beach. These fundamentals include love and companionship, which statistics tell us are in short supply. Today millions have achieved the once optimistic dream of living like minor pharaohs and kings in suburban tract homes and McMansions, yet inadvertently many find themselves separated from the companionship and community that are basic human cravings.

The irony is that we know how to fix at least some of what makes us on edge. For instance, we know we shouldn’t drive gas-guzzling SUVs and that we should stop looking at endless perfect kitchens, too-perfect influencers, and 20-second rants on TikTok. We can feel helpless even as new ideas and innovations proliferate. This may explain one of the great contradictions of this age of arrhythmia—one demonstrated in a 2023 UNESCO global survey about climate change that questioned 3,000 young people from 80 different countries, aged 16 to 24. Not surprisingly, 57% were “eco-anxious.” But an astonishing 67% were “eco-optimistic,” meaning many were both anxious and hopeful.

Me too.

All this anxiety and optimism have been hard on our hearts—literally and metaphorically. Too much worry can cause this fragile muscle to break down, to lose its rhythm. So can too much of modern life. Cardiovascular disease remains the No. 1 killer of adults, in the US and most of the world, with someone in America dying of it every 33 seconds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The incidence of A-fib has tripled in the past 50 years (possibly because we’re diagnosing it more); it afflicted almost 50 million people globally in 2016.

For me, after that initial attack on Martha’s Vineyard, the A-fib episodes kept coming…

For the rest of the essay and to find out what happened to my heart and what may happen to more of us in the near future, click here.

XXXXX

________

From My Archives: MIT Technology Review

What I saw through a microscope—my own heart cells, and they were beating strong and true.

When this article appeared in 2011 my heart was beating more steadily. I was writing about a revolutionary new technology to create stem cells and asked a company in Wisconsin used my blood cells to create a stem line that was then tweaked to grow heart cells. I’m including this in the politics and heart issue for two reasons. One is that if I ever need new and healthy heart cells that beat steadily, the technique and technology described here might one day be the answer. The other reason is the politics of the early 2000s, when stem cells were derived from human embryos for research, a process opposed by conservative groups. When President George W. Bush partially banned fetal stem cell research in 2001, scientists like evolutionary biologist James Thompson, described in the story, developed a new technique that allowed the creation of stem cells that do not come from fetal cells, a method that’s now an integral part of biomedical research and therapeutics.

Growing Heart Cells Just for Me

Blood cells can now be transformed into stem cells and then made into any cell in the body. Recently, I peered through a microscope at “my” heart cells as they pulsed in a petri dish, perhaps to be used to test new drugs and to better predict and treat disease

By David Ewing Duncan—August 23, 2011

Peering through a microscope in Madison, Wisconsin, I watched my heart cells beat in a petri dish. Looking like glowing red shrimp without tails, they pulsated and moved very slowly toward one another. Left for several hours, I was told, these cardiomyocytes would coalesce into blobs trying to form a heart. Flanking me were scientists who had conducted experiments that they hoped would reveal whether my heart cells are healthy, whether they’re unusually sensitive to drugs, and whether they get overly stressed when I’m bounding up a flight of stairs.

It was snowing outside the office-park windows of Cellular Dynamics International (CDI), where I was observing an intimate demonstration of how stem-cell technologies may one day combine with personal genomics and personal medicine. I was the first journalist to undergo experiments designed to see if the four-year-old process that creates induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can yield insight into the functioning and fate of a healthy individual’s heart cells. Similar tests could be run on lab-grown brain and liver cells, or eventually on any of the more than 200 cell types found in humans. “This is the next step in personalized medicine: being able to test drugs and other factors on different cell types,” said Chris Parker, CDI’s chief commercial officer, looking over my shoulder.

CDI scientists created the little piece of my heart by taking cells from my blood and reprogramming them so that they reverted to a pluripotent state, which means they are able to grow into any cell type in the body. The science that makes this possible comes from the lab of CDI cofounder and stem-cell pioneer James Thomson of the University of Wisconsin, the leader of one of two teams that discovered the iPS-cell process in 2007. (The other effort was led by Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University.) The results are similar to the special cells that appear in embryos a few days after fertilization.

Since late 2008, the company has been manufacturing cardiomyocytes and mailing the frozen cells on dry ice to academic scientists to study how these cells work, and to researchers in the pharmaceutical industry to use in early tests of drug candidates. One important reason to use the cells is that they could reveal whether drugs are toxic to the heart, information that other types of testing can miss. “Several drugs have made it to the market that have cardiotoxic profiles, and that’s unacceptable,” Parker says. He says that the cardiomyocytes derived from iPS cells are a huge improvement over the cadaver cells sometimes used to test potential drug compounds. Unlike the cadaver cells, IPS-generated cells beat realistically and can be supplied in large quantities on demand. What’s more, iPS-generated cells can have the same genetic makeup as the patients they came from, which is a huge advantage in tailoring drugs and treatments to individuals. These made-to-order cells are not cheap, however. Cellular Dynamics’ CEO, Robert Palay, says they cost about $1,500 for a standard vial of 1.5 million cells.

An especially sensational prospect is that iPS cells could be transplanted into patients so they could regenerate diseased or damaged spines, brains, hearts, or other tissue—a proposition that is particularly enticing because these cells wouldn’t be rejected by the host’s body. They could also defuse the political controversy around embryonic stem cells, because they may one day make it possible to harvest pluripotent cells without destroying a human embryo…

Pluripotent pioneer: University of Wisconsin biologist James Thomson cofounded Cellular Dynamics International in 2007 after developing a method of reprogramming ordinary human cells to create induced pluripotent stem cells, which can give rise to any cell type. Thomson has since helped pioneer the use of iPS cells in drug development.

Making Heart Cells for Me

I launched my own iPS journey in a small Quest Diagnostics clinic on a leafy street in San Francisco. Wrapping a rubber tube around my arm, the phlebotomist stuck in a needle to withdraw several vials of blood that would be shipped on ice to Madison. Once they got to CDI, technicians cracked open my white blood cells and used a bioengineered retrovirus to introduce “master transcription” genes into their DNA. These genes reprogrammed the cells so that when they replicated, the results were pluripotent cells rather than more white blood cells. Their transformation into functioning iPS cells took several months of coaxing, purification, and verification that cost about $15,000, which the company paid on my behalf. Once my pluripotent cell line was humming along, the scientists at CDI tweaked a few cells to make them differentiate into three types of heart cells—which I first saw pulsing in a video clip they e-mailed to me.

In Madison, nearly a year after giving up my blood, I was just a bit anxious as I stared at my beating heart cells. I was about to get a rundown on the experiments CDI had performed to demonstrate what these little bundles of bioengineered cytoplasm and nuclei might say about my health and my sensitivity to various drugs…

For the rest of the article click here.

______

Video of Talk

Video: Playing Mambo with My Heart

Delivered to a “Quantified Self” Meet-Up, delivered by David Ewing Duncan, December 14, 2011

Click Here for You Tube Video of Talk

This talk describes how a company in Wisconsin drew blood from me and converted cells into stem cells, a process called Induced Pluripotent Stem cells. When I gave this talk, IPS cells were brand new and were beginning to replace embryonic stem cells that came from fetuses and were highly controversial. The company, called Cellular Dynamic International, was co-founded by University of Wisconsin’s Jamie Thompson, a developmental biologist and a pioneer of the IPS process. Thomson kindly agreed to have his company create an IPS cell line for me and to convert these stem cells into heart cells and neurons. In the talk, I describe the science and the process and what it was like to see “my” heart cells beating through a microscope. The CDI team ran tox-screens on my cells to see how tolerant they were to higher and higher doses of a common chemotherapy that is known to be harsh to heart cells. Check out the talk for details.

XXXXX